Trip report: Spanish adventures in ecotoxicology

Original post: https://urbancaracaldiet.wordpress.com/2019/07/03/trip-report-spanish-adventures-in-ecotoxicology/

The caracal samples finally arrived on the 10th May 2019! I was so relieved when Pablo (the fantastic lab technician at IREC) handed me the box. We immediately unpacked the samples and set to testing the clean-up methods we’d been practicing on three caracal samples. Looking at the results of these tests we found the recoveries of compounds worked best with the more traditional, cheaper sulphuric acid clean-up method.

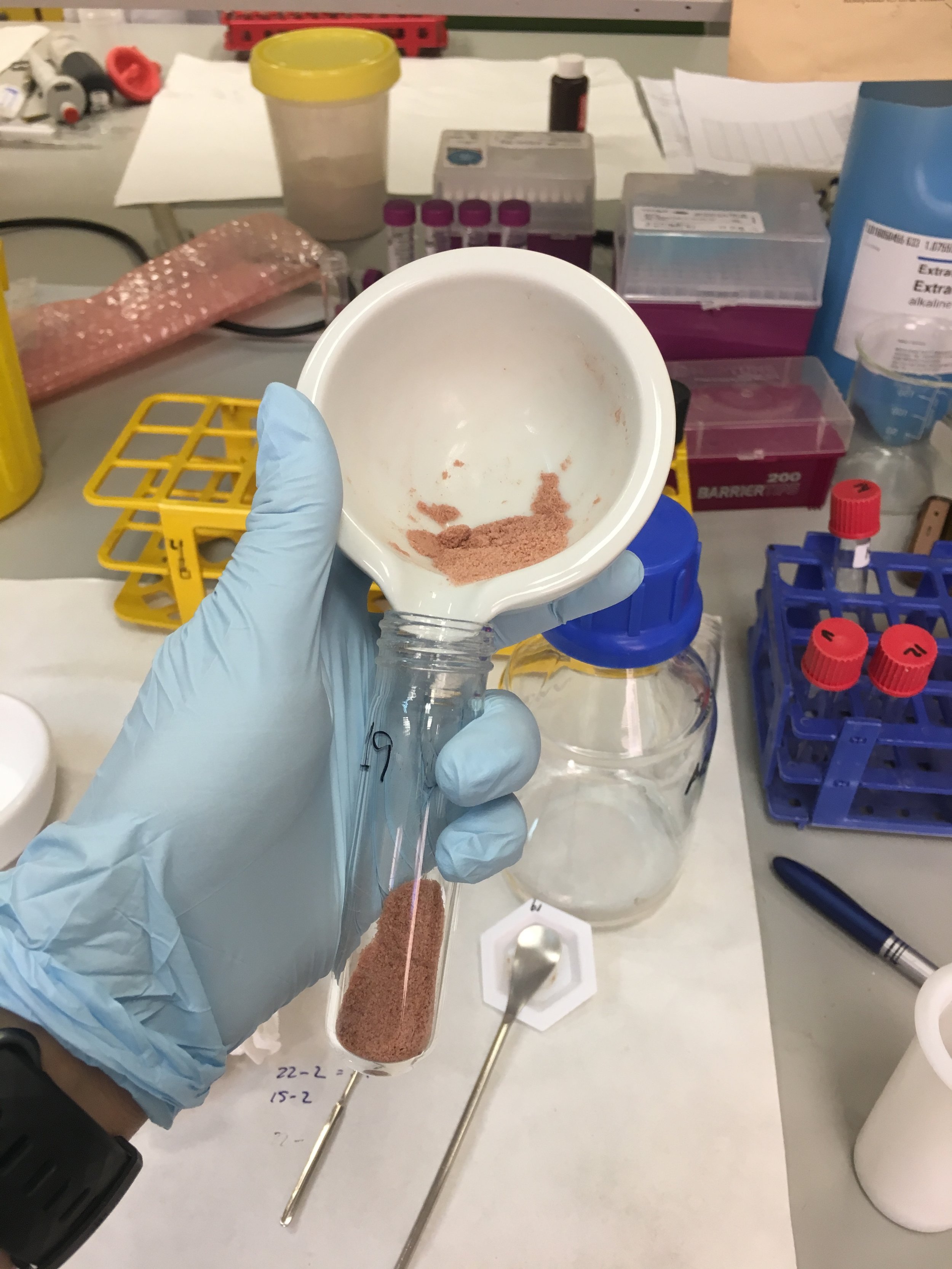

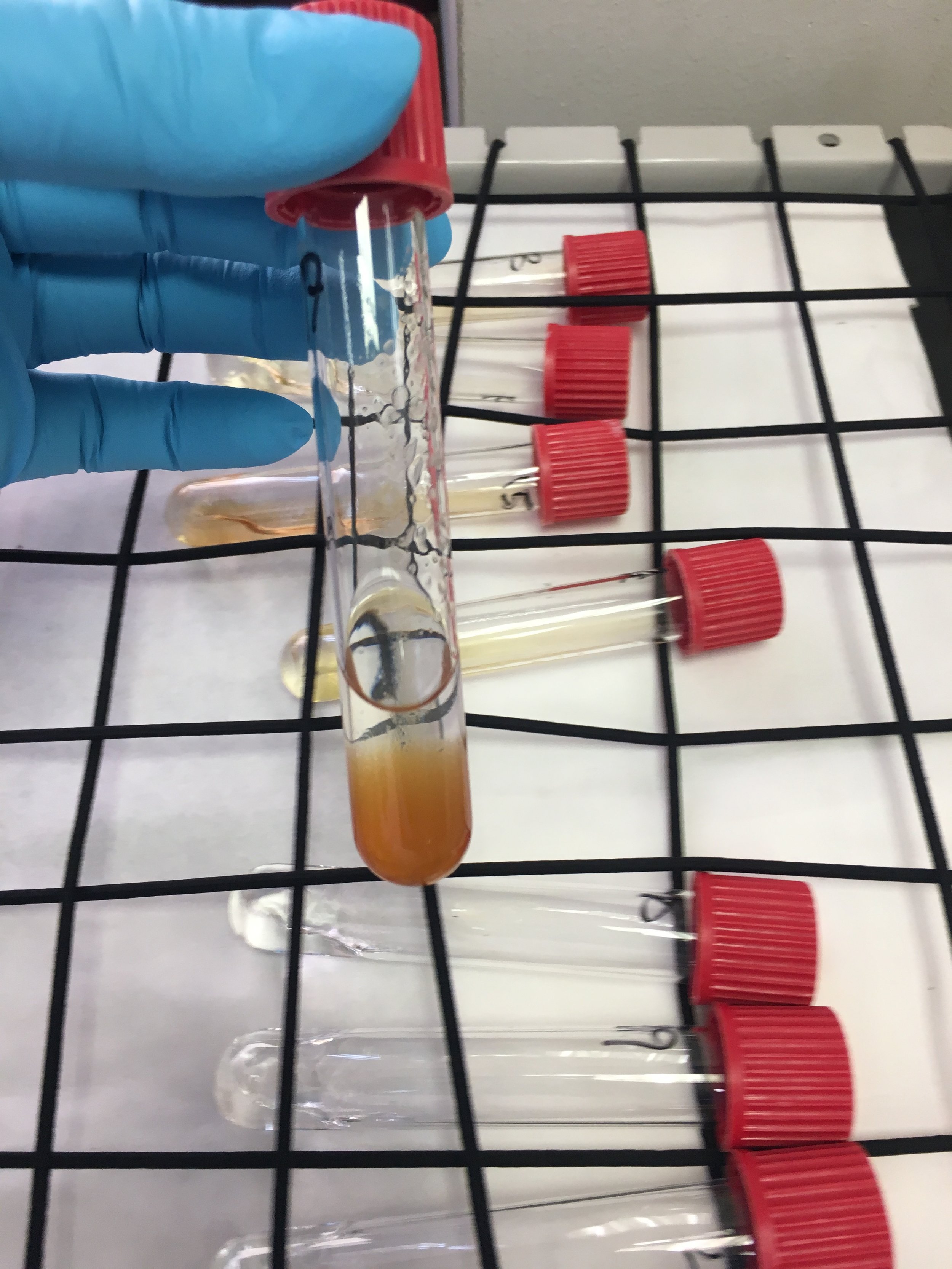

The caracal blood samples, which had been liquid to start with, had been solidified into “morcilla” (Spanish blood pudding) by the time they got to us! We had had to add ethanol and exposure to extreme heat as part of the requirements of the Spanish Ministry of Agriculture’s import permit. This meant rather than pipetting anything, we had to weigh the blood to 0.5g per sample for extraction. However, we soon realised these recoveries were not good enough and had to increase this to 1g to improve detection. Over the next weeks we used an n-hexane extraction followed by a sulphuric-acid clean-up method to obtain extracts of caracal blood and fat tissue. In total, I tested 69 blood and 25 fat samples for organochlorine pollutant (e.g. DDT and PCBs) exposure. The fat content of the samples was estimated using gravimetry (i.e. weighing the empty tube and then weighing it again after the sample extraction when the fat residue in it had dried, and then calculating the difference) to give the results per lipid weight.

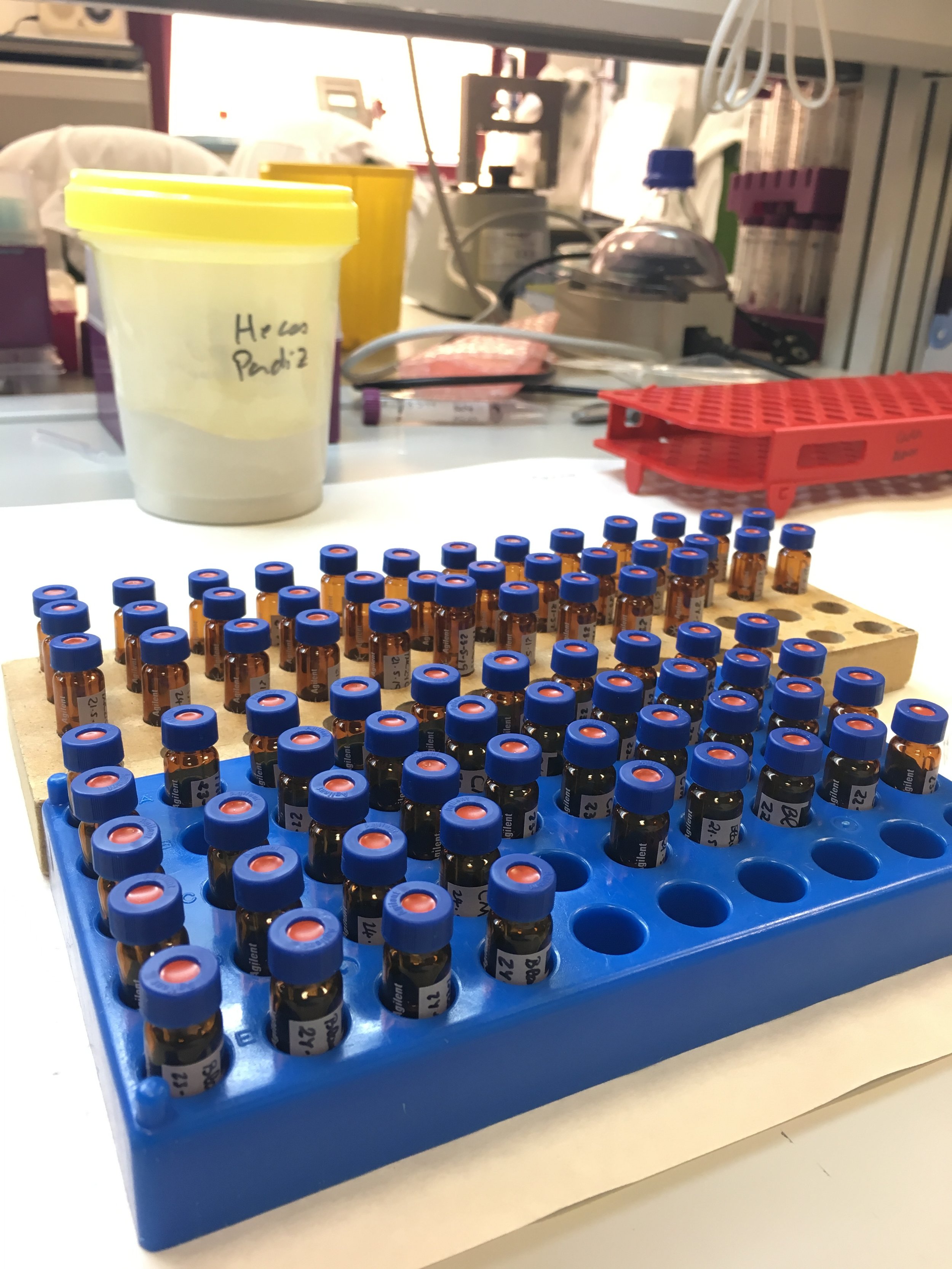

While in the process of doing these extractions, there was a slight hiccup. We had planned to run samples in the Gas Chromatography with Electron Capture Detector (GC-ECD) system as we extracted them. But in the very first sample of our very first run the sulphuric acid was not completely removed from the sample extract, which damaged the column of the GC-ECD system. It was quite a face-palm moment, as not only was the machine broken but we couldn’t even see any results at all because the first sample killed everything. We had to order a new column, which took several days to arrive and to install and recalibrate. Once the GC-ECD system was functional, we ran the extracts again with relevant pesticide standards for calibration (something rather arbitrarily called “Pesticide Mix 13″), which took five days to complete. When looking at the chromatographs (i.e. the graph produced by the GC that shows peaks of compounds over time; the compounds can be identified by looking at the time at which they were made, called the ‘”retention time”) we found several large peaks in many of the samples that were not identified by GC-ECD. These peaks may represent polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs, organic compounds containing bromine that are used widely as flame retardants) in the samples that were not present in our internal standard but may also have been cholesterol or similar large compounds. We did identify peaks of the organochlorines that were in our internal standard: the most important being DDT and it’s metabolite DDE, and several PCBs (PCB138, 153 and 180; the number refers to the number of chlorines and the position of those chlorines in the compound). In order to confirm the identification of both these unknown peaks and known peaks we will have to run the extracts again using GC-Mass Spectrometry (MS) . Once the organochlorine testing is complete, the same sample extracts are to be used to test for PBDEs (which I’m very excited about). This will only take place when the IREC obtains the equipment for Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) in late Spanish summer, probably in October.

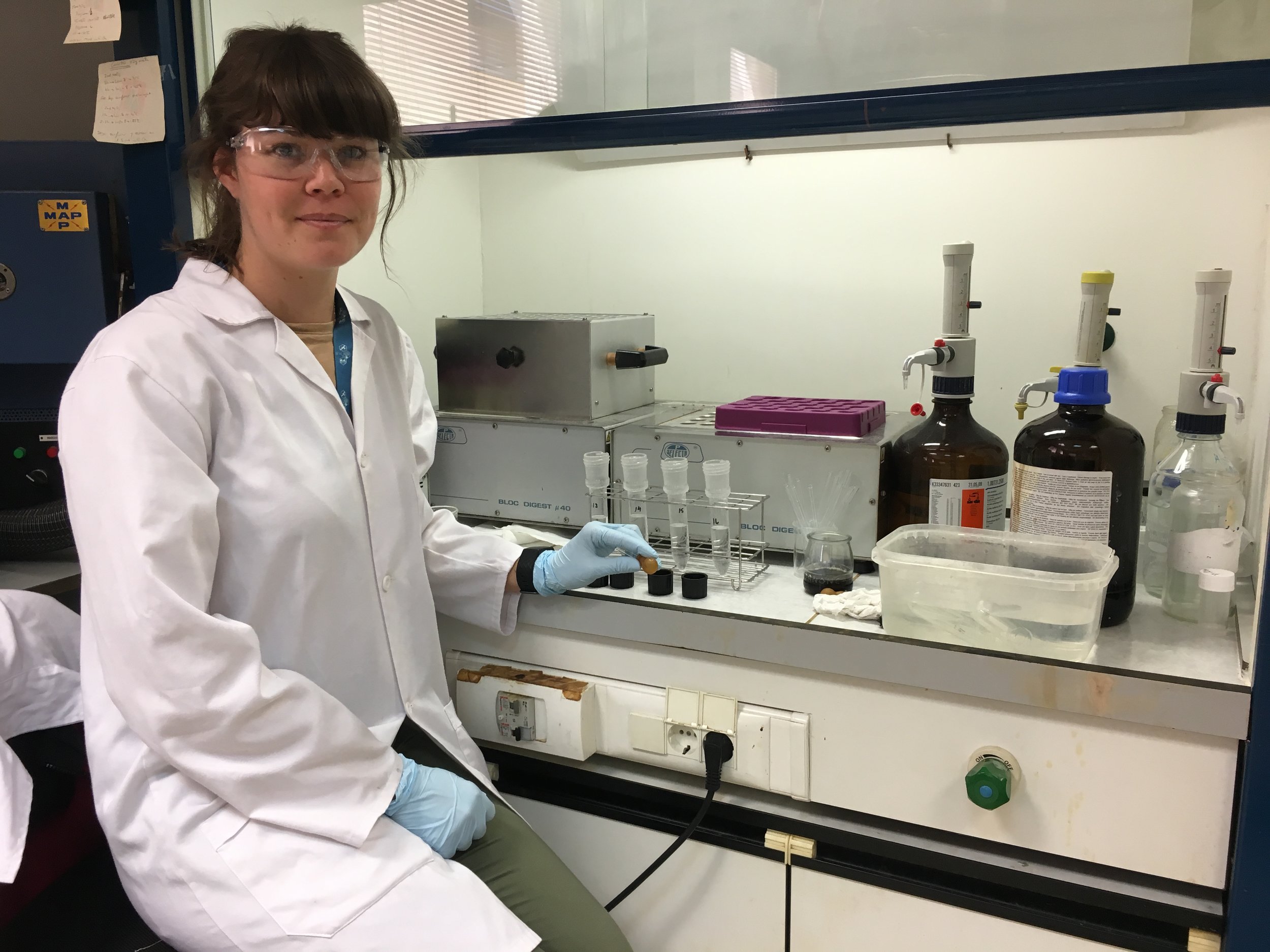

When the extractions were complete, I also started the acid digestions necessary for testing for the presence and concentrations of heavy metals in the blood samples. While we didn’t initially plan to do this, I’m really pleased we can include this analysis, as heavy metals are a critical component to pollution in urban areas. The method uses temperature-controlled microwave heating of the lyophilised (i.e. freeze dried) sample with nitric acid and hydrogen peroxide for determination of metals by spectroscopic methods. This testing will also take place when the ICP-MS equipment arrives, which will allow the simultaneous testing of multiple heavy metals together.

While at my short stay at IREC I tried my best to get involved in some other projects: I assisted in the necropsy of a weasel; I donated blood to a tick-borne diseases project; I helped in a project on monitoring European swallow nests, and assisted in a project ringing and sampling European quails. I also travelled to Elche on the east coast of Spain in the province of Alicante to assist in a European eagle owl monitoring project. We checked on four nests with fledgling owls and retrieved camera traps previously set up to monitor diet. At IREC I met other researchers working on similar projects on Spanish wildlife: vultures, Egyptian mongoose, Eurasian otter, Iberian lynx, wild boar, European rabbits and least weasels. I also got to experience some of Spain’s natural areas, such as the Cabañeros National Park near Toledo, and Cabo de Gata-Níjar Natural Park in Almería. On the 16th May I presented my PhD research and my plans for the data I was collecting to the IREC. I was informed that the talk was to be filmed and lived-streamed for those not able to attend in person. This was a terrifying prospect for me, as I’m not only camera-shy, but also hugely intimidated by public speaking. I later discovered that this was a first attempt for UCLM and they’d never tried live-streaming anything before. Nevertheless, the talk was quite successful, with about 15 people connecting to watch remotely in addition to approximately 20 people who attended in person. Despite my fears, I realised this was a good opportunity to share my ideas with the institute and I received many enthusiastic questions both immediately after the talk but also in the weeks afterwards. I found that everyone I met was very interested in the research taking place in South Africa, the kinds of wildlife conservation issues we have to tackle and how this differed from most places in Europe. I also realised that there is relatively little ecotoxicology work being done on South African wildlife compared to most European countries, and I hope that my visit will have catalysed more collaboration and increased focus in this really fascinating (to me) and important field.

The preliminary data has been sent to me since my return to South Africa and I am in the process of summarising and analysing them. Once I’ve looked at the basic patterns, I’m planning to model the concentrations with several environmental covariates (e.g. proportion wetland or agricultural cover in caracal home range, protected area status, transformer density), as well as sex, age and various bloodwork variables to identify patterns of contamination with land use type and between demographic groups and physiological condition. I’m so enthusiastic about this dataset that I’m going to be hard-pressed to focus on getting work done on my other chapters! I really enjoyed everything about this first experience of ecotoxicology research: the labwork was rewarding, the people were amazing, the equipment was impressive, and the results promise to be very interesting! This (too-)short stay in Spain gave me the opportunity to broaden my horizons in not only in terms of academic networking and witnessing the scale and type of science taking place in Europe, but also arming me with a new skillset and data that will undoubtably strengthen my thesis conclusions.

Note: this text is a modified version of an international travel report originally written for the University of Cape Town’s Postgraduate Funding Office because I received a Smartt Memorial Scholarship for the short stay at UCLM/IREC in Ciudad Real, Spain. The testing of caracal samples was funded with a grant from the Table Mountain Fund.