Blog post archive

Welcome to the No Free Lunches blog! These posts follow the work of Gabriella Leighton, who wrote it as a PhD student at UCT, while working with the Urban Caracal Project to understand how urbanisation affects the foraging ecology of Cape Town caracals. For the original personal blog visit: urbancaracaldiet.wordpress.com. Here is an archive of previous posts:

-

July 2019

- Jul 10, 2019 Blog post archive Jul 10, 2019

- Jul 3, 2019 Trip report: Spanish adventures in ecotoxicology Jul 3, 2019

-

May 2019

- May 8, 2019 Urban Caracal Project goes to Spain! May 8, 2019

-

December 2018

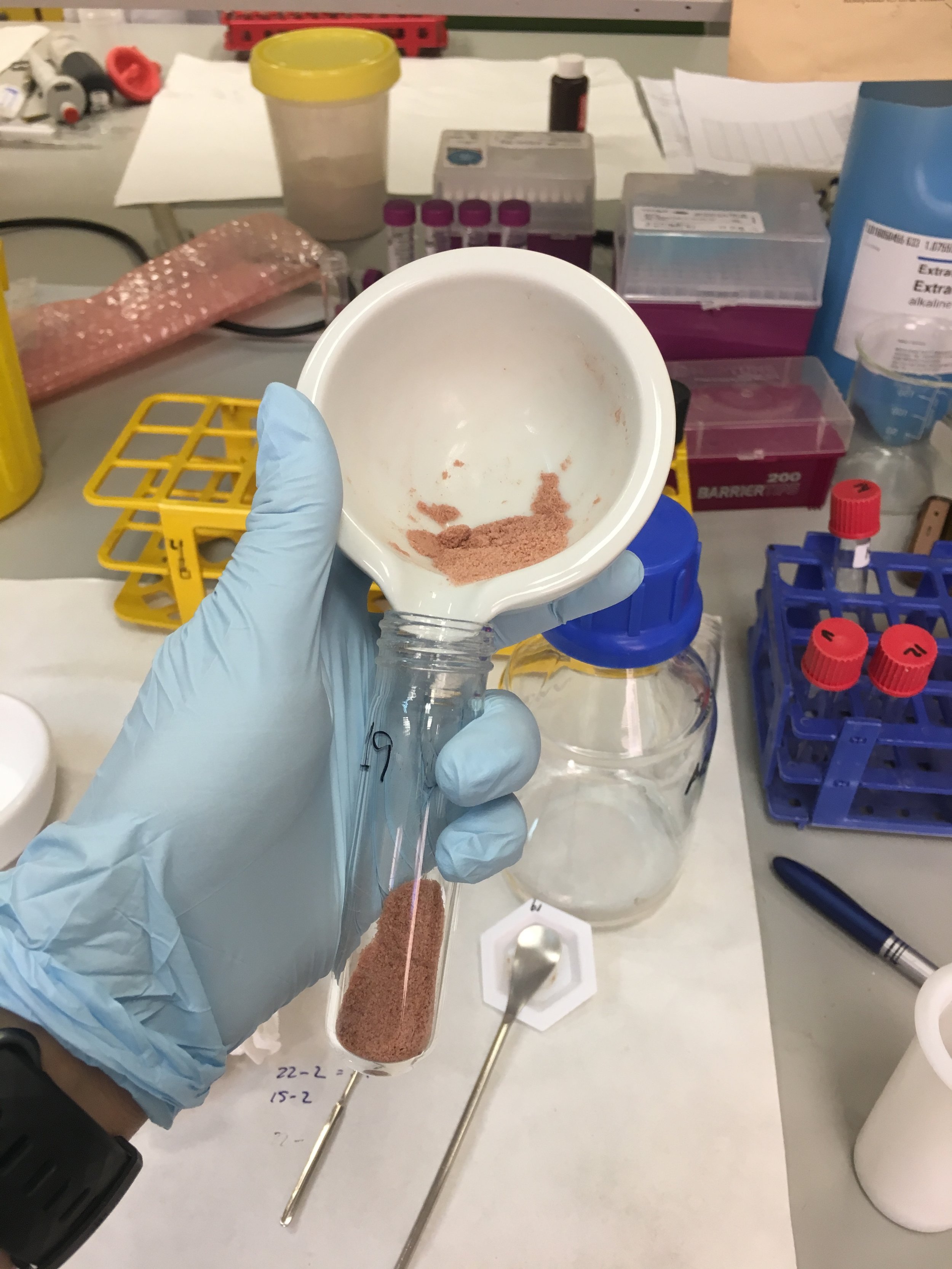

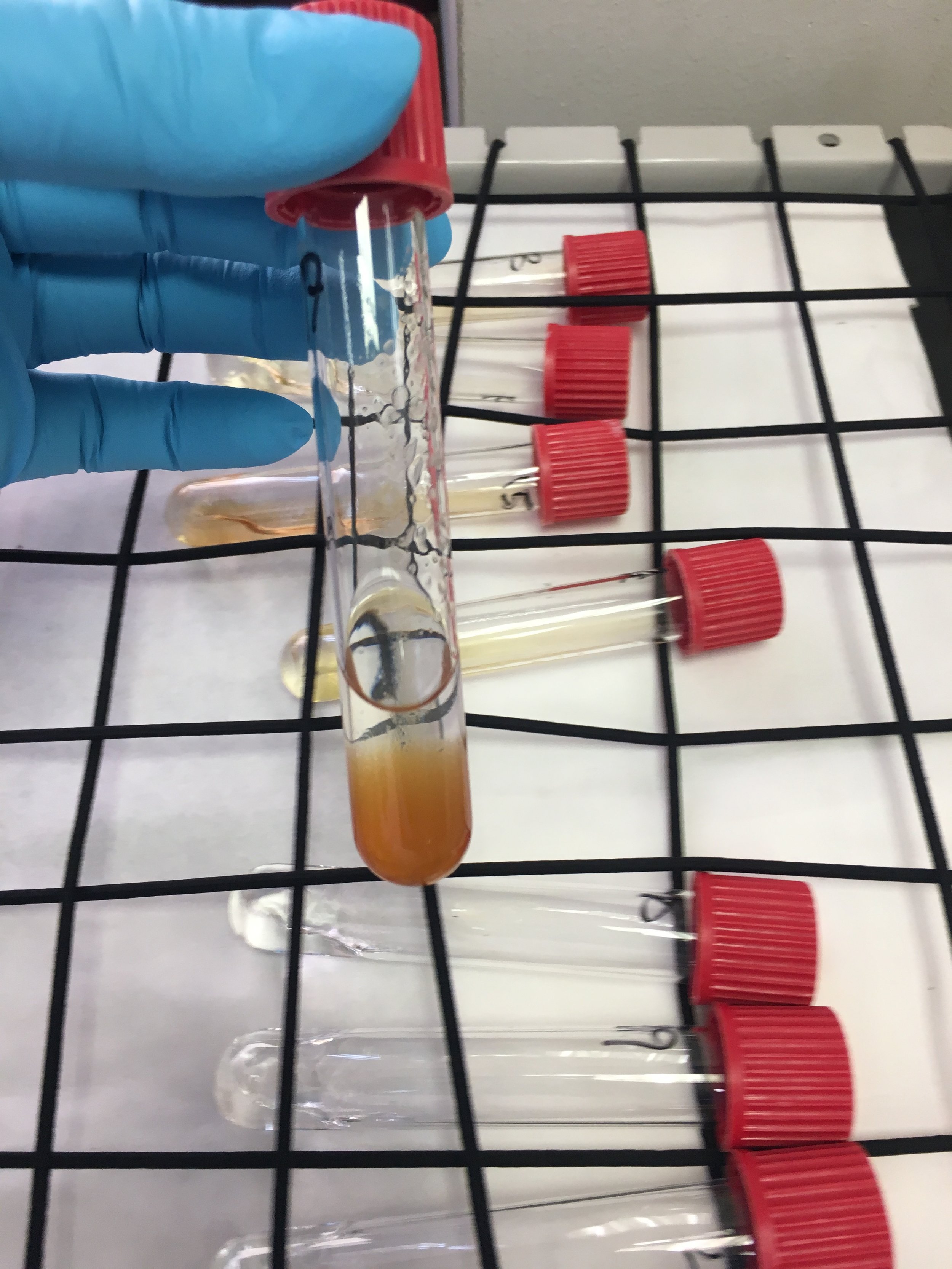

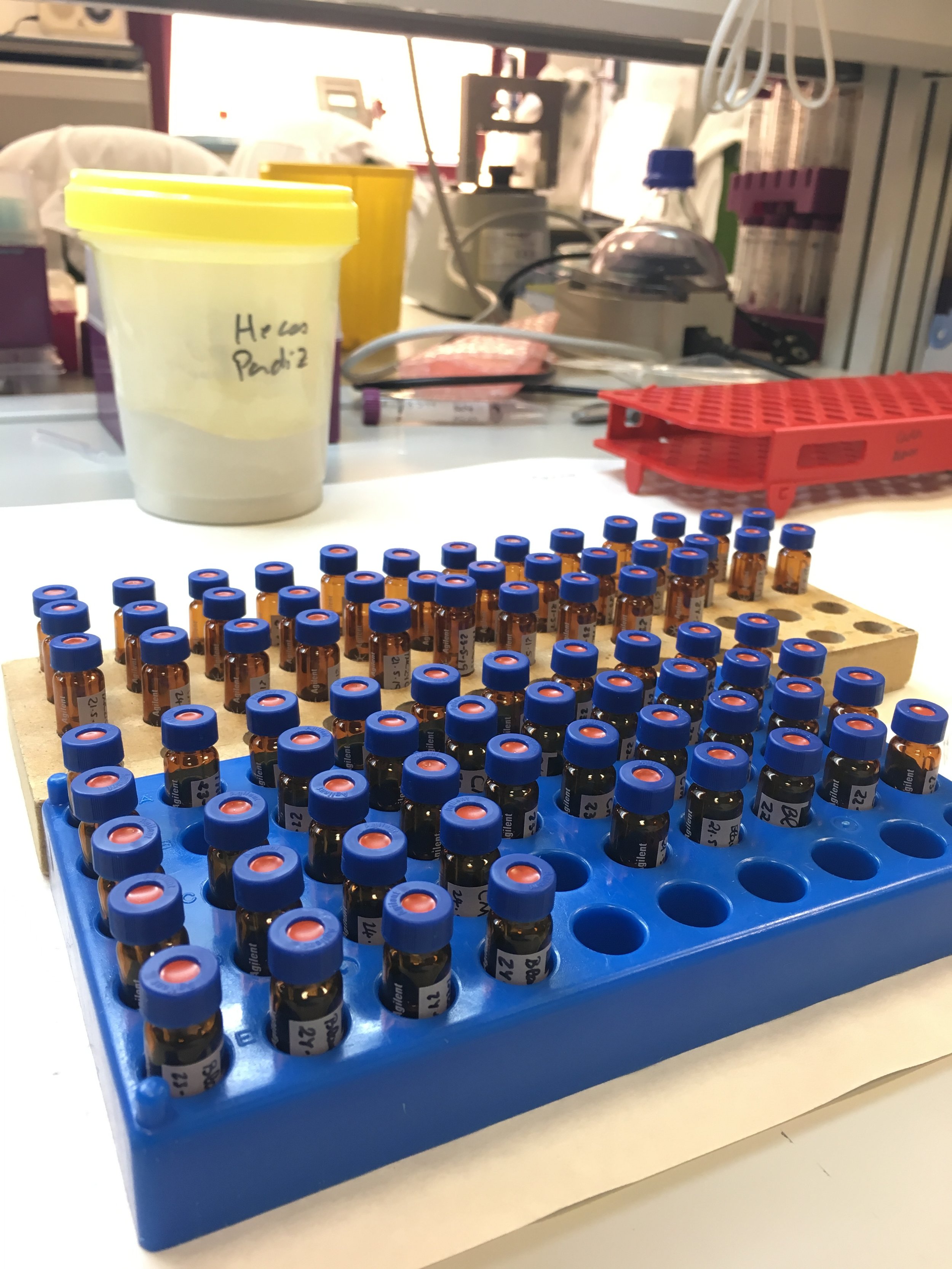

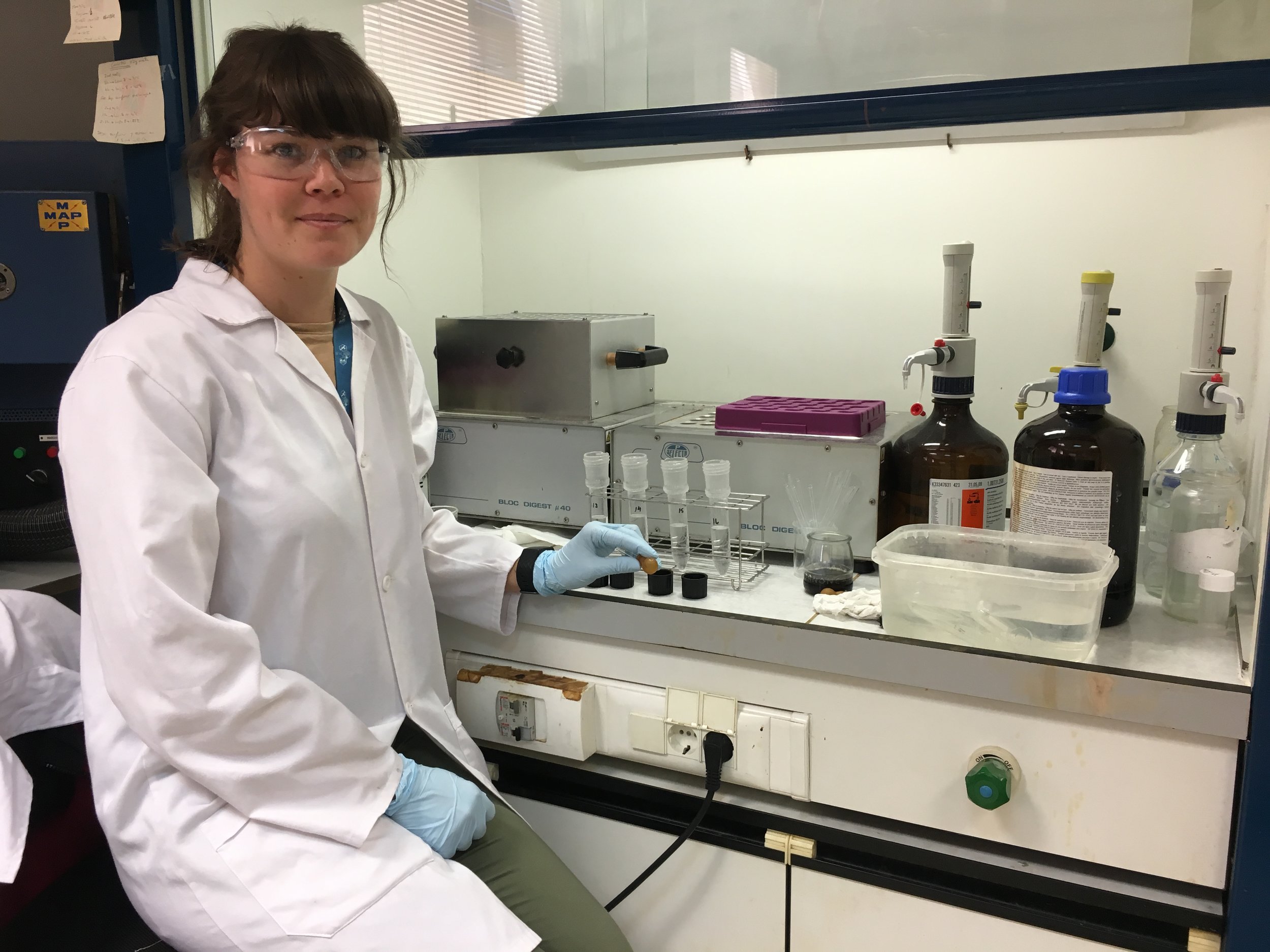

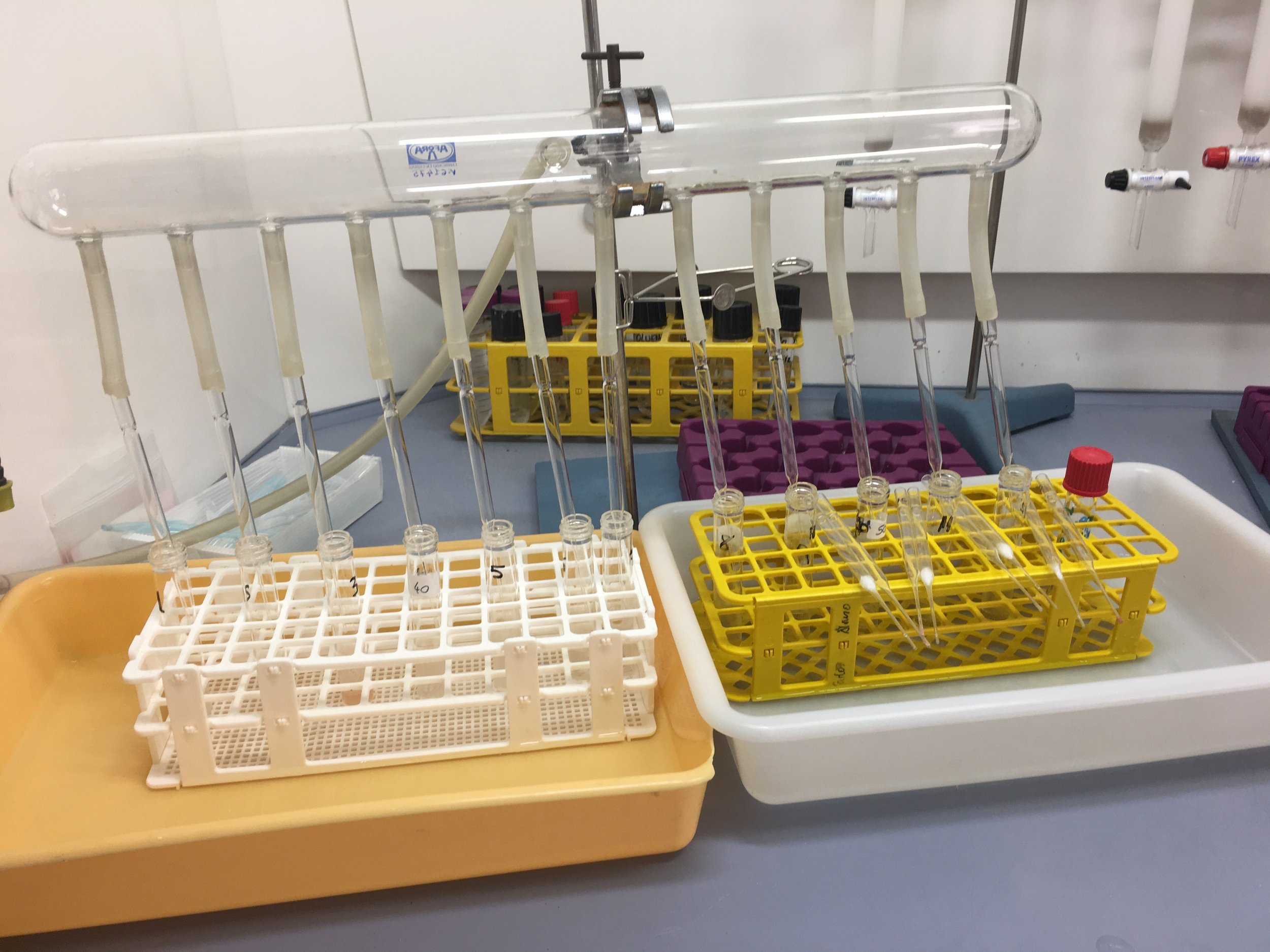

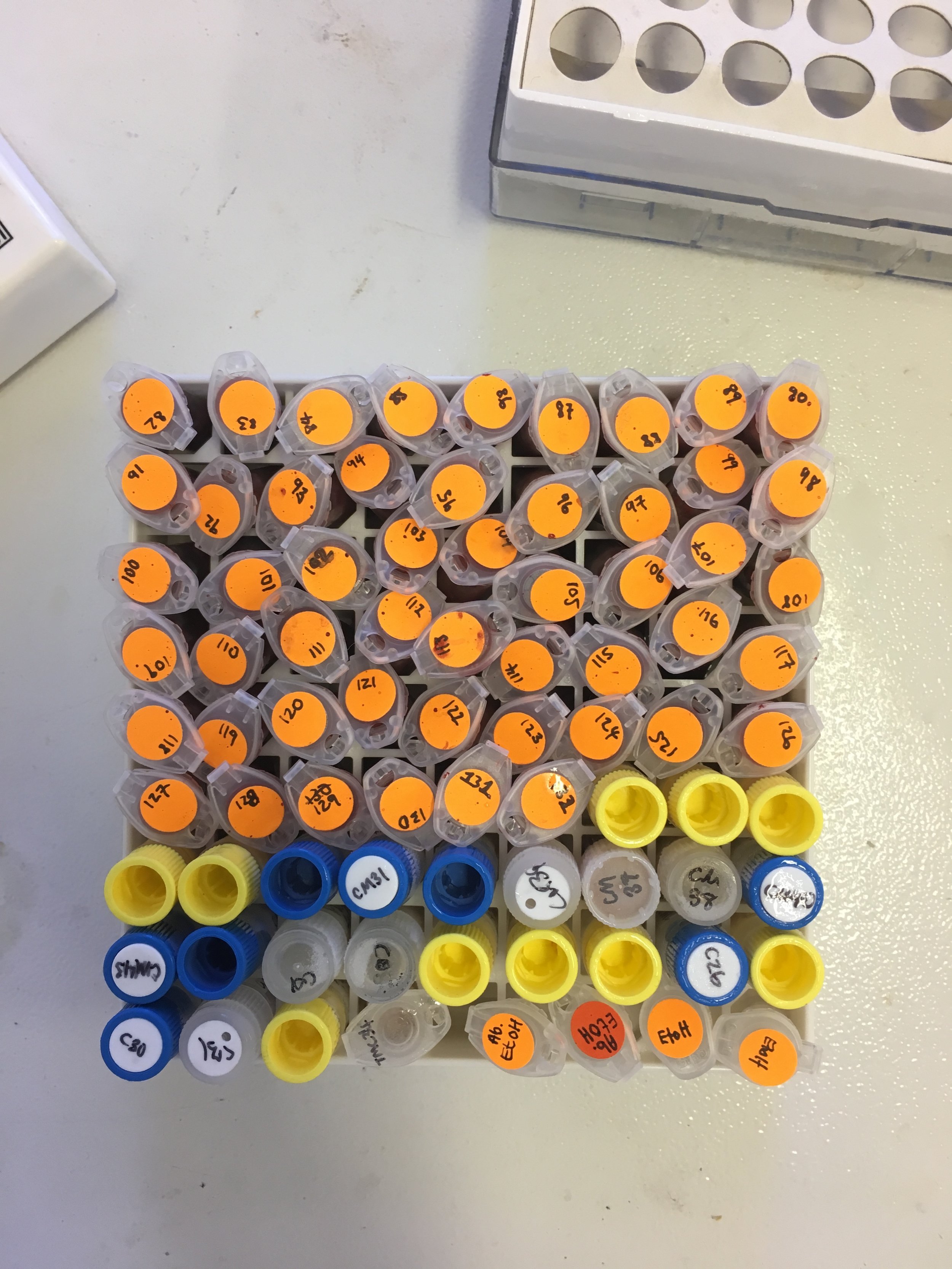

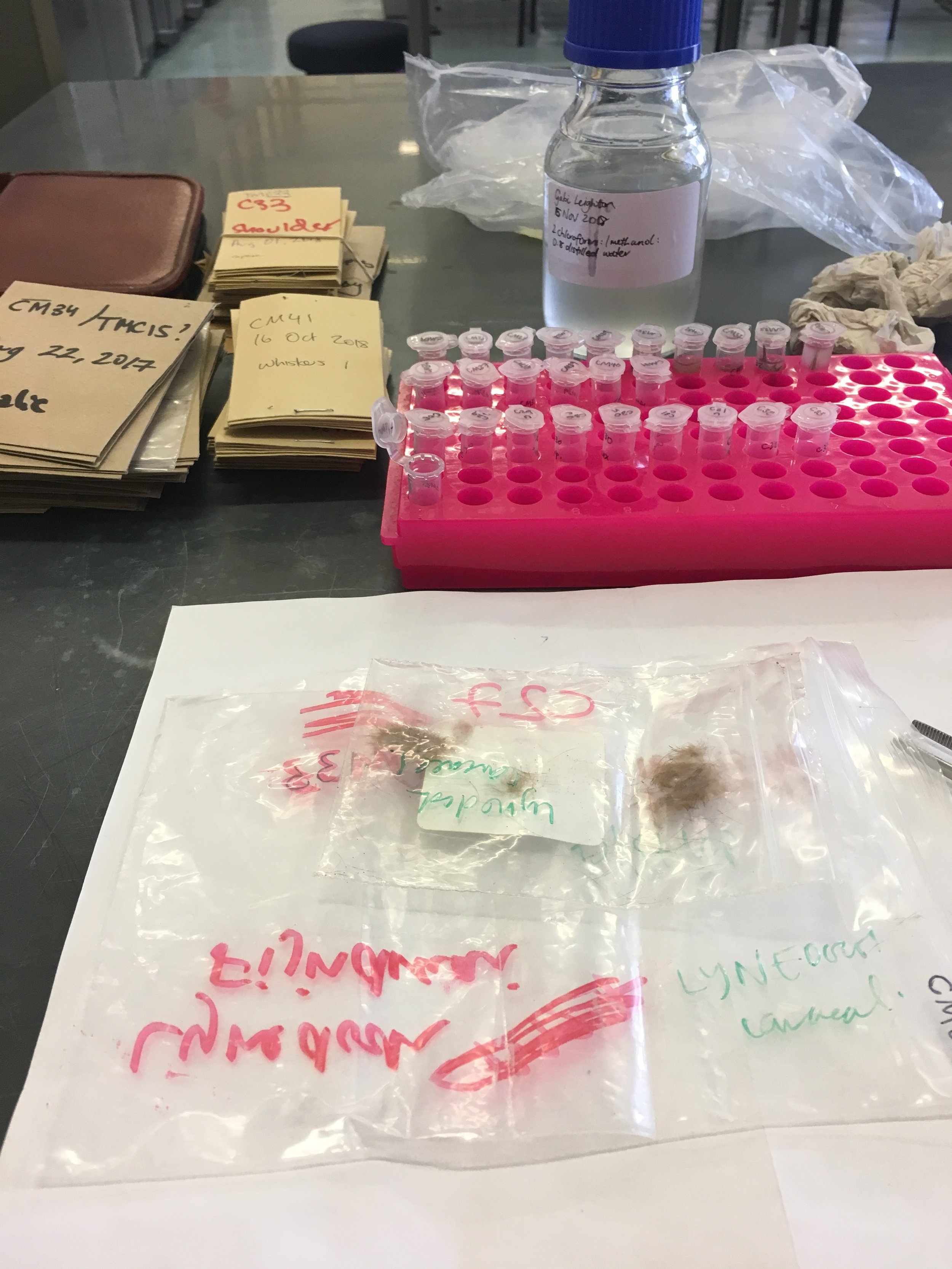

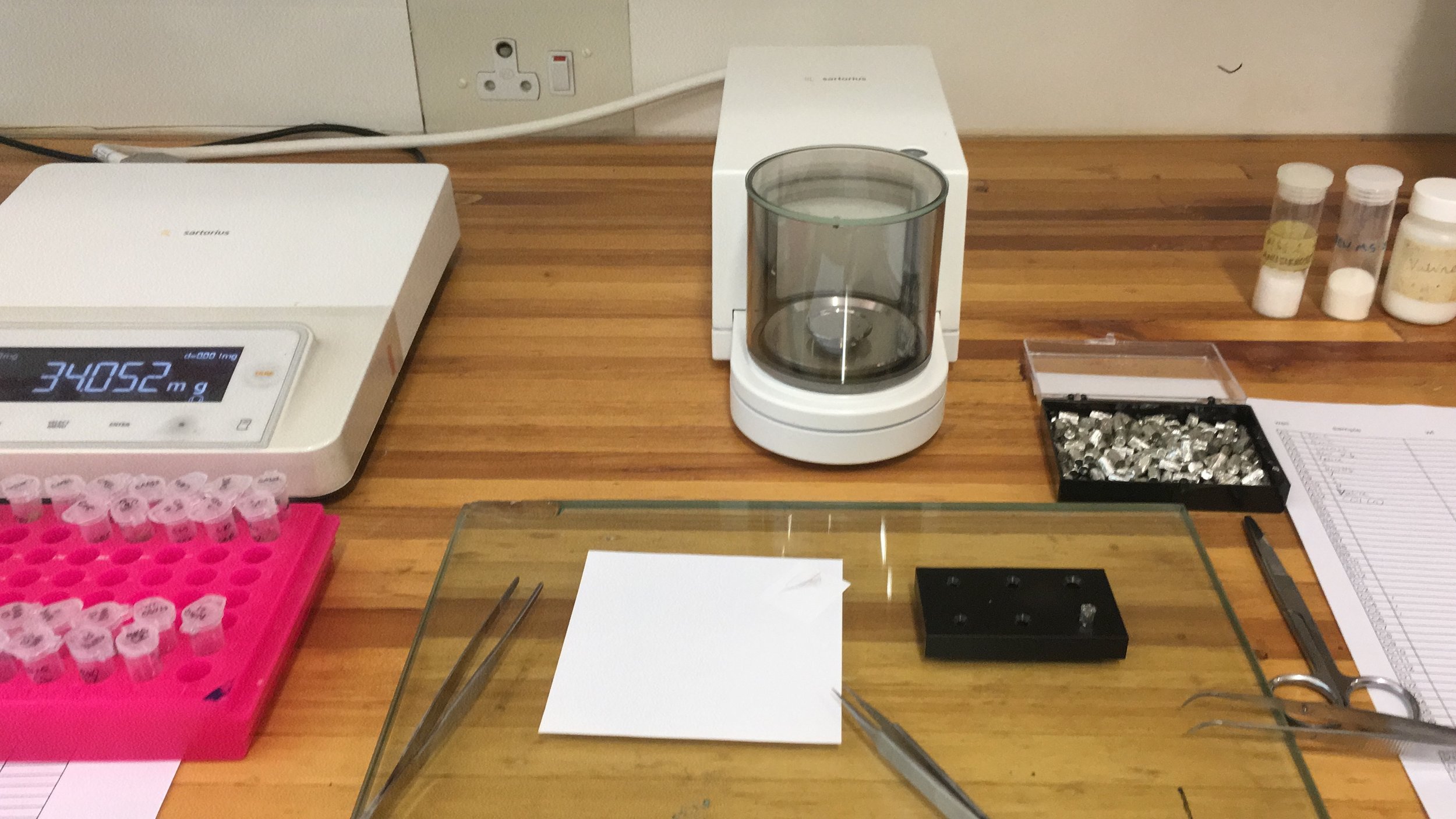

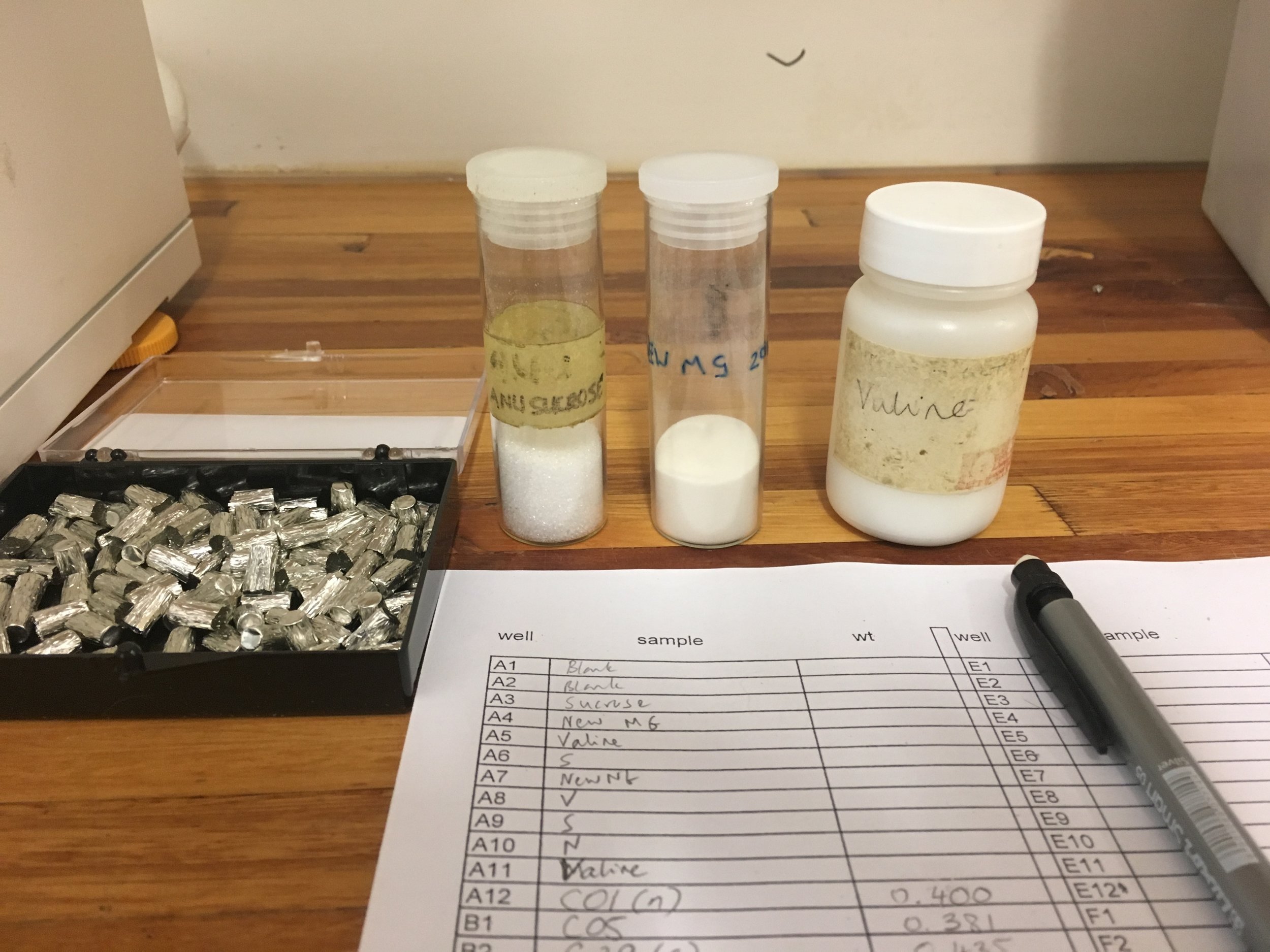

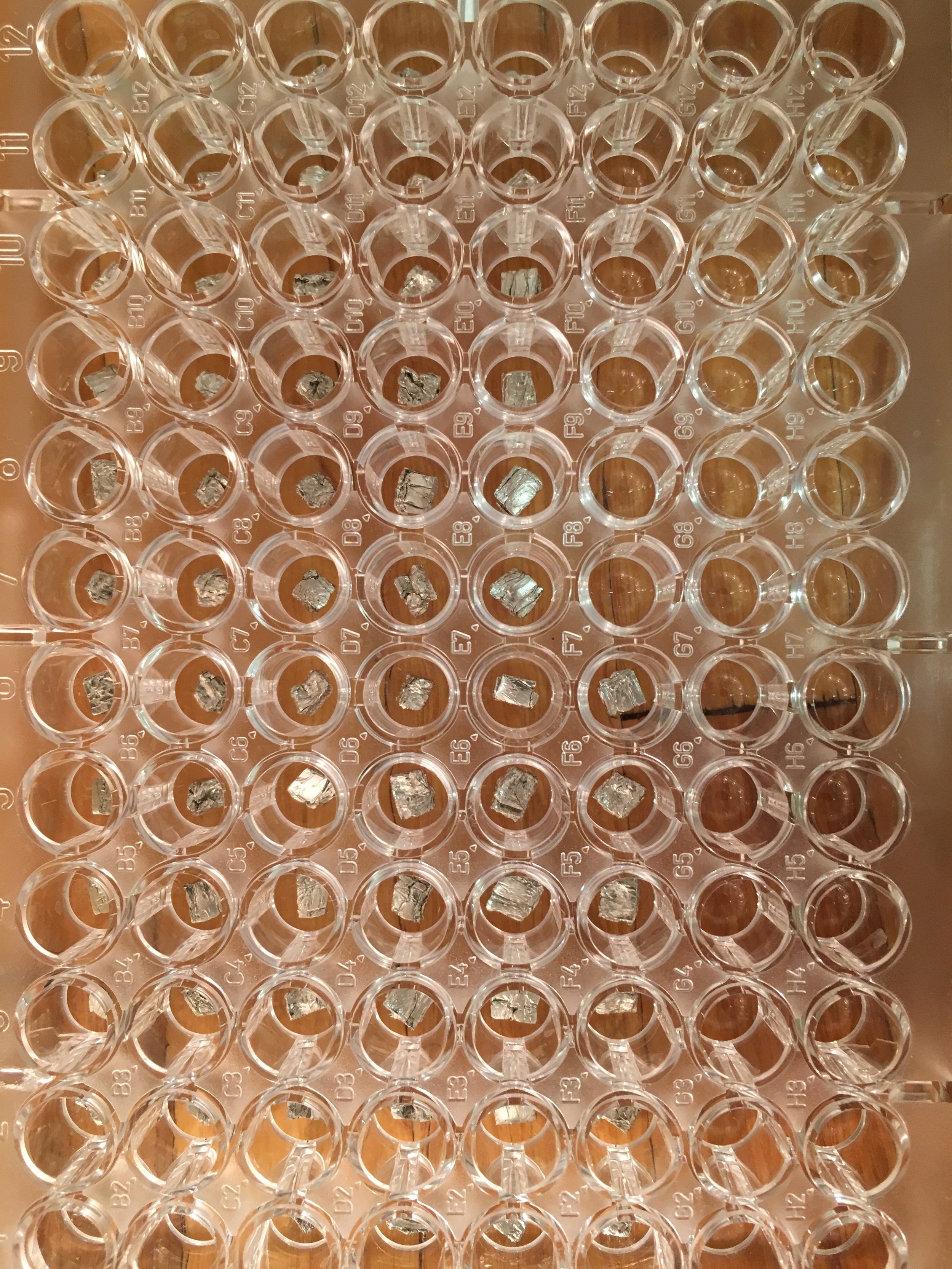

- Dec 20, 2018 Starting that stable isotope stuff (finally) Dec 20, 2018

-

September 2018

- Sep 17, 2018 URBIO Conference 2018 Sep 17, 2018

-

May 2018

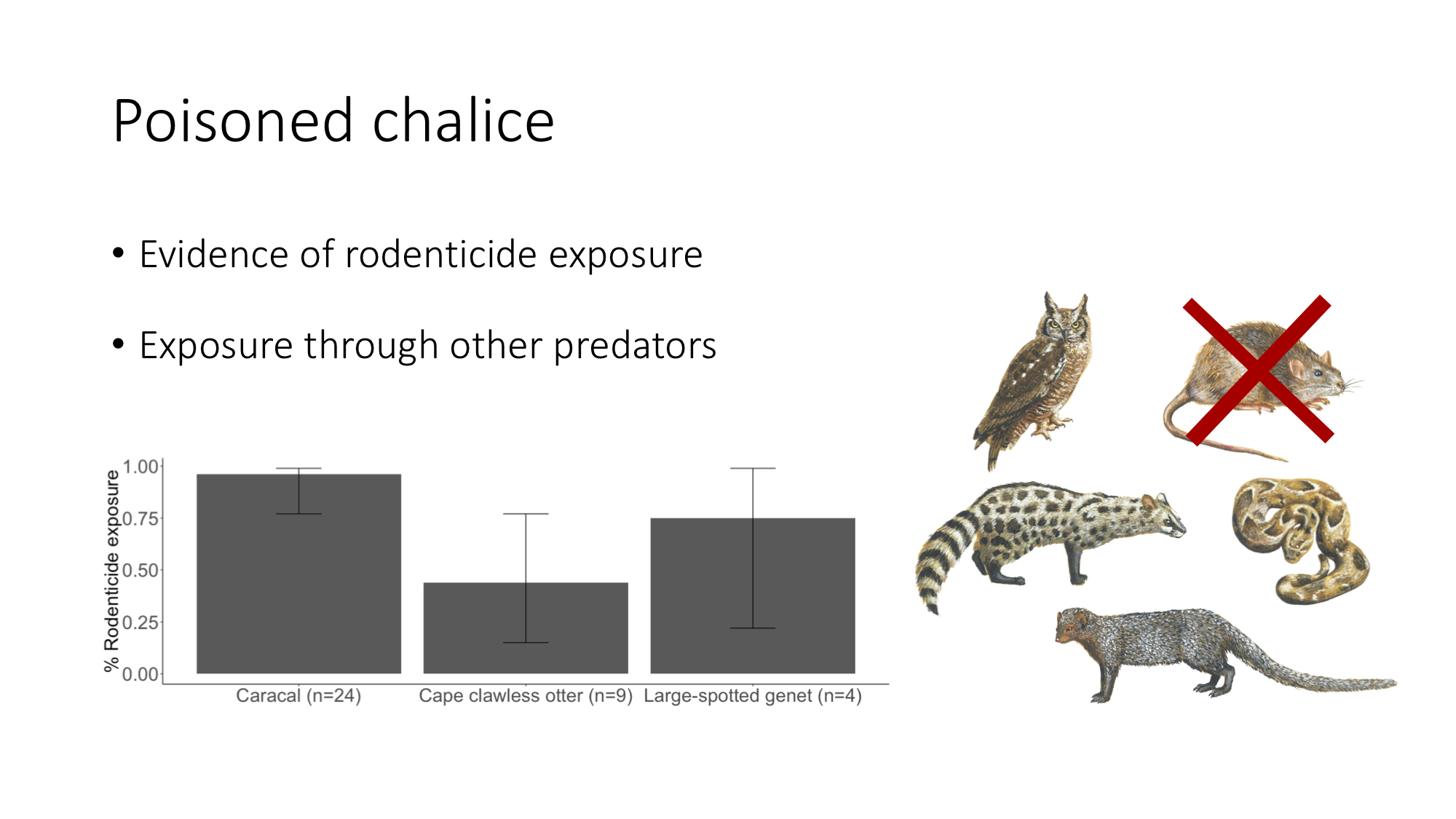

- May 21, 2018 The big ‘upgrade’ May 21, 2018

-

September 2017

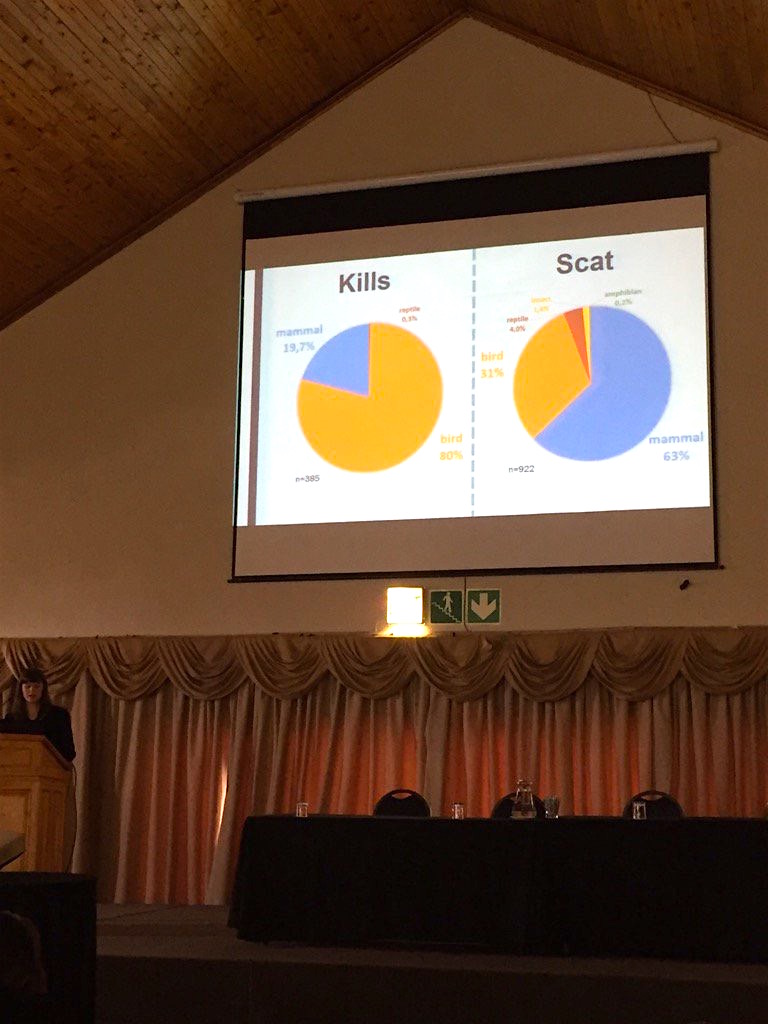

- Sep 16, 2017 SAWMA symposium 2017 Sep 16, 2017

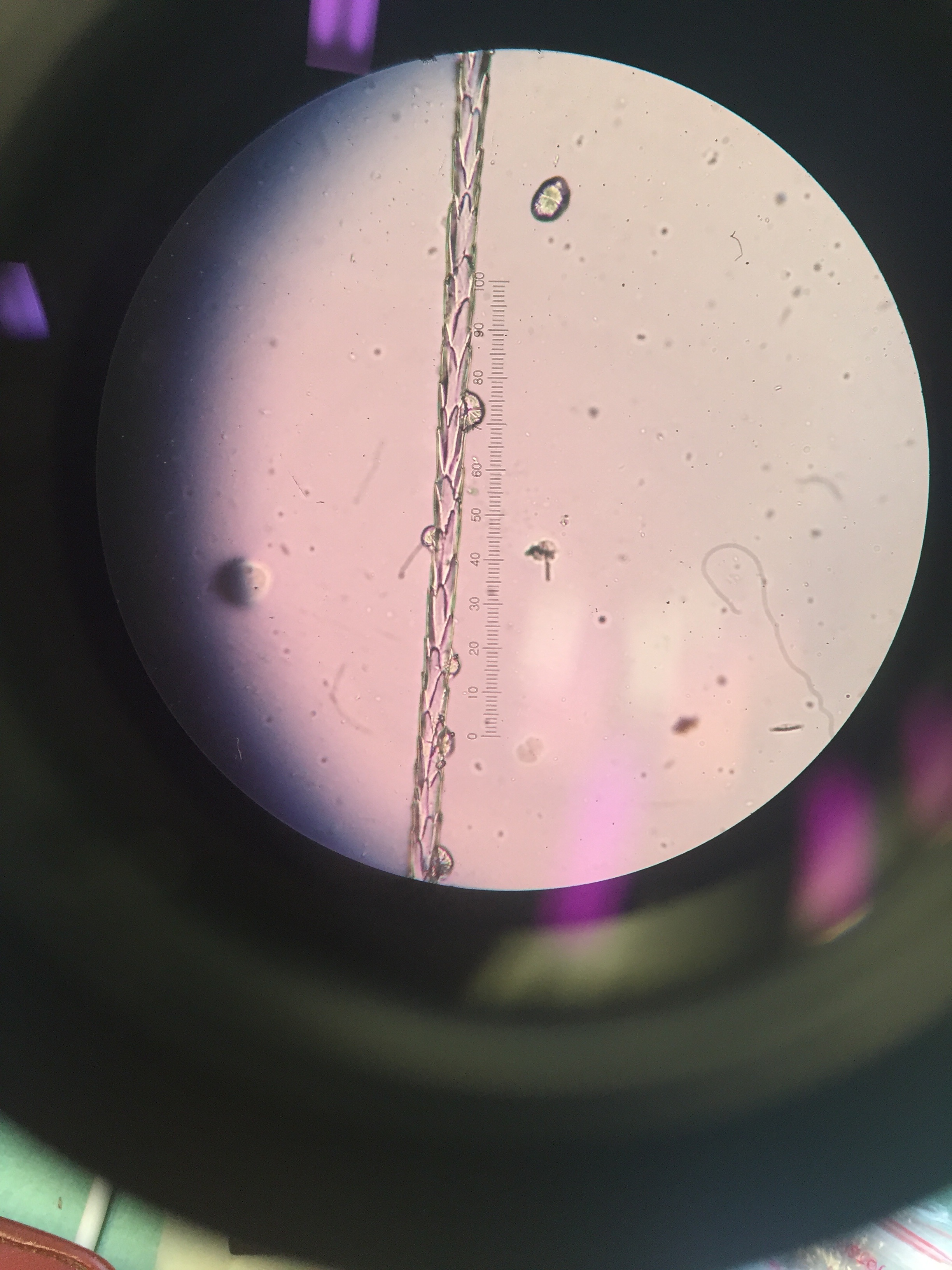

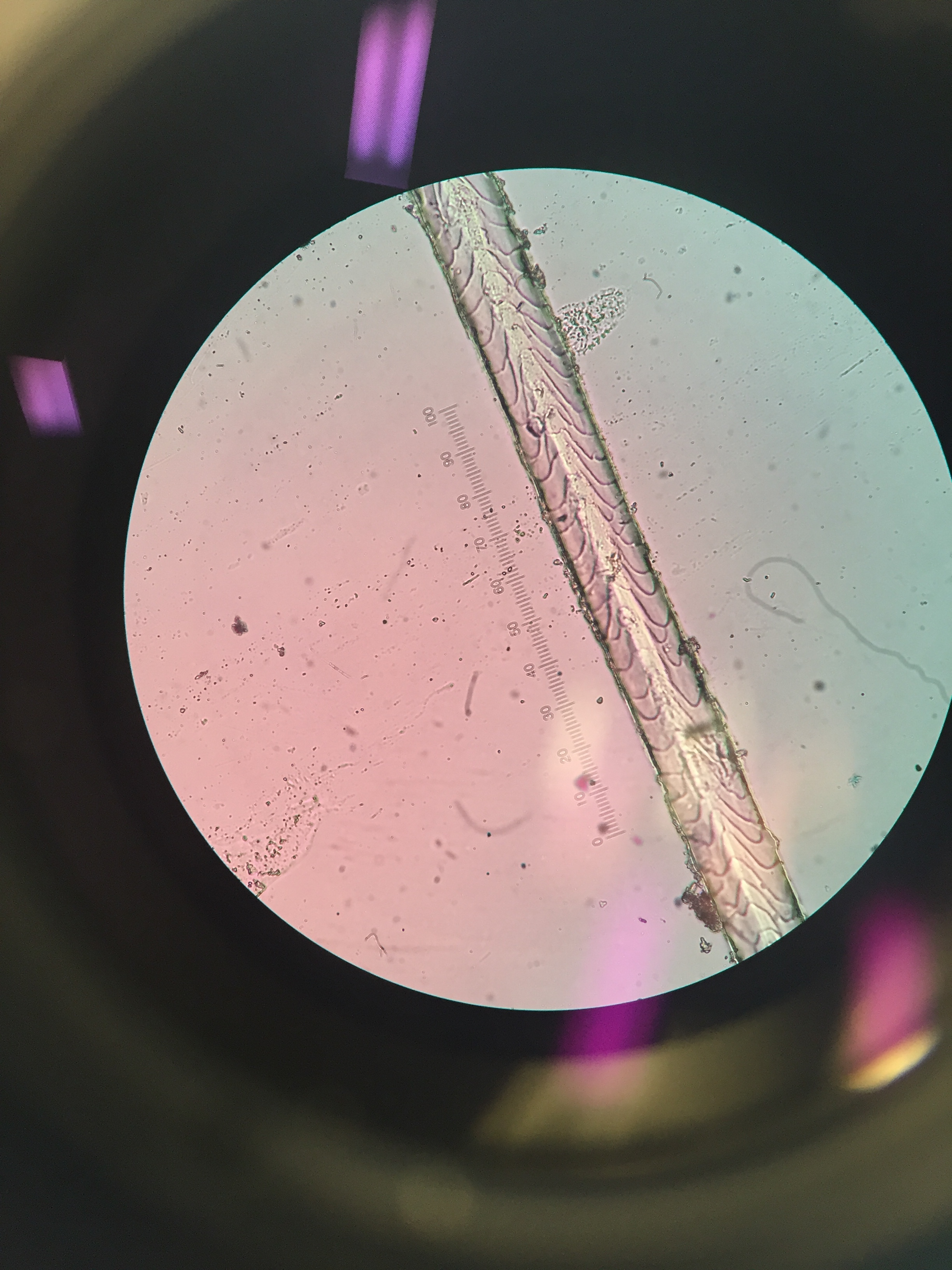

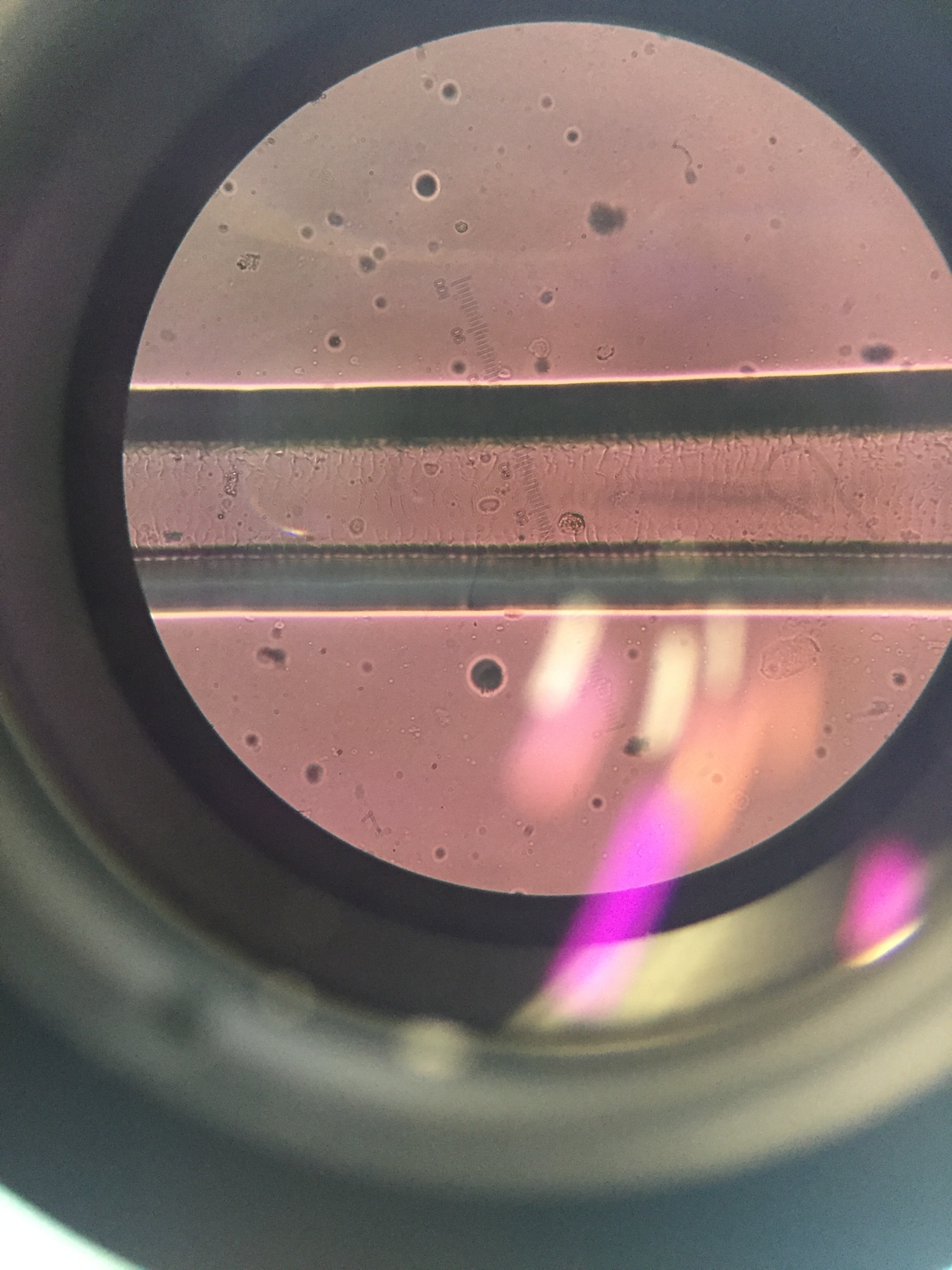

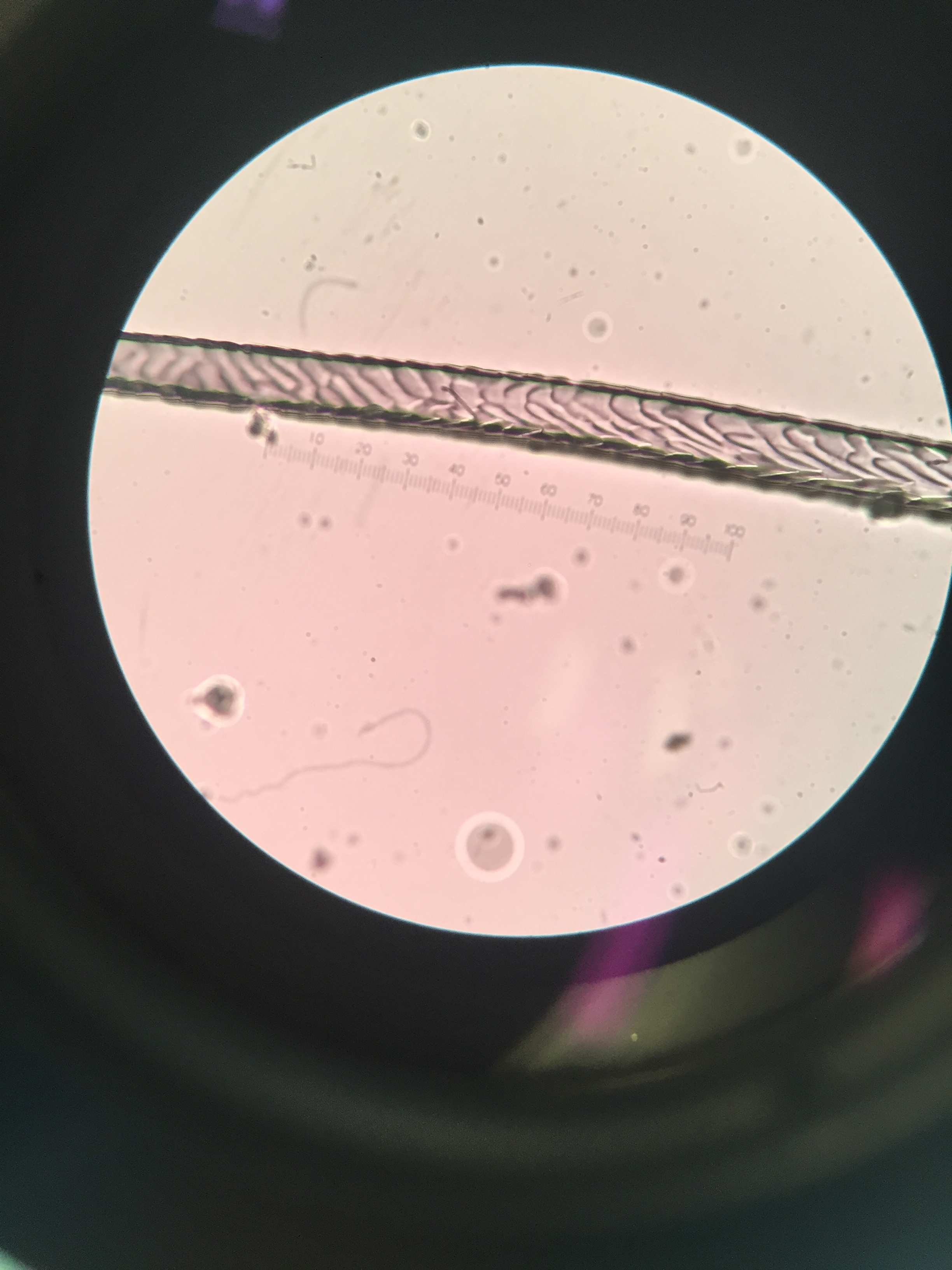

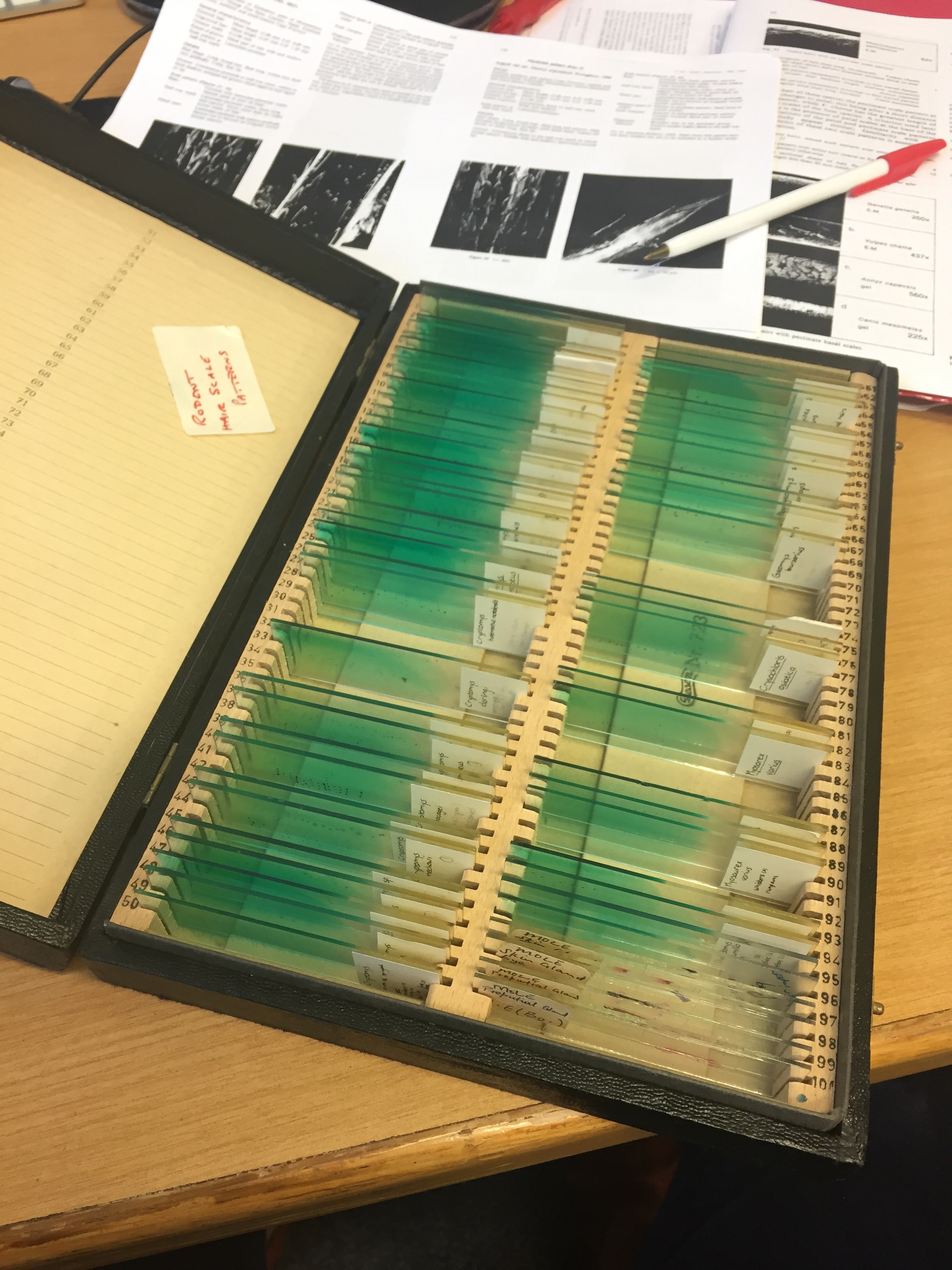

- Sep 7, 2017 Impressions: hair identification Sep 7, 2017

-

June 2017

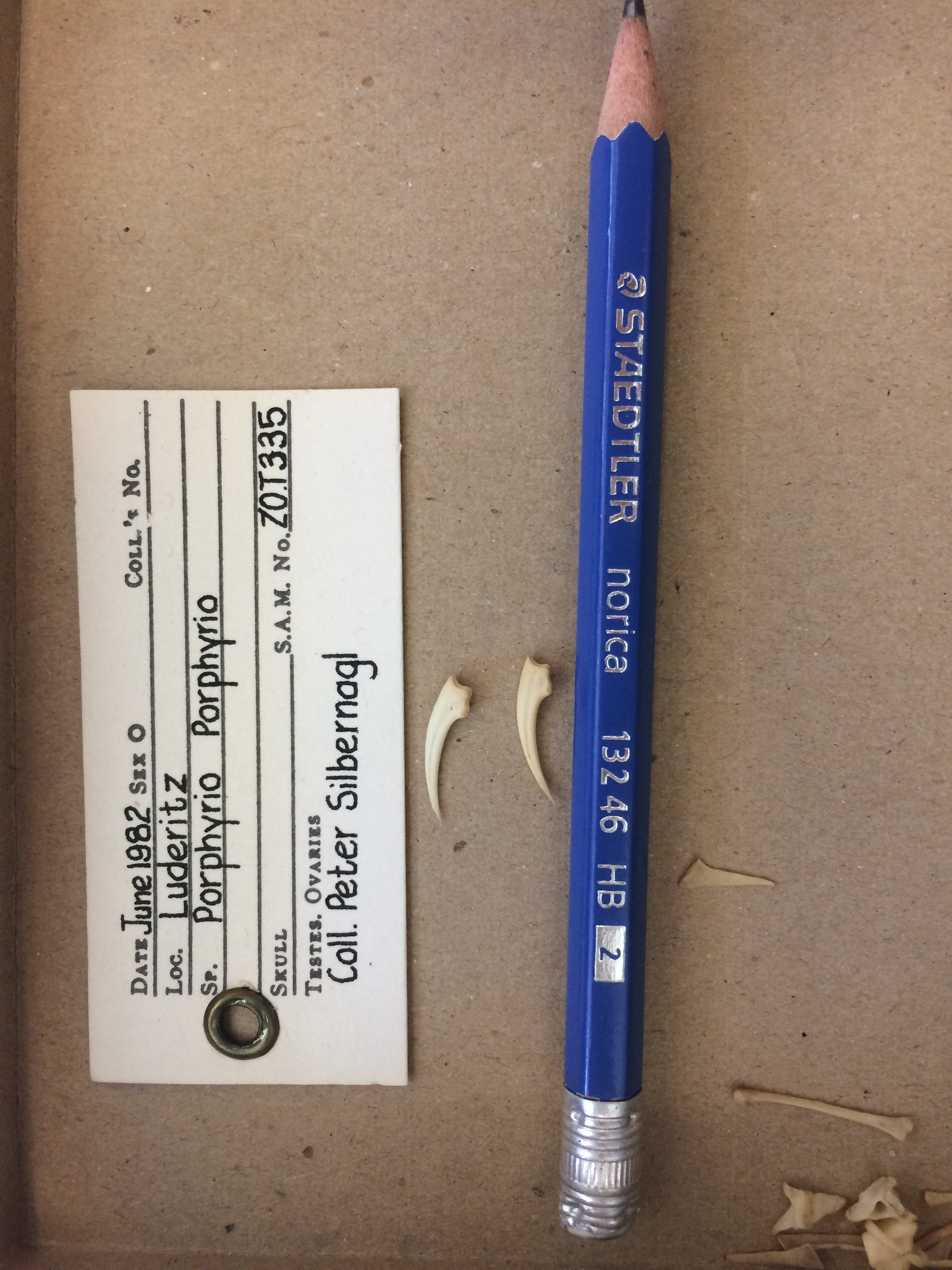

- Jun 13, 2017 Of mice and museums Jun 13, 2017

-

May 2017

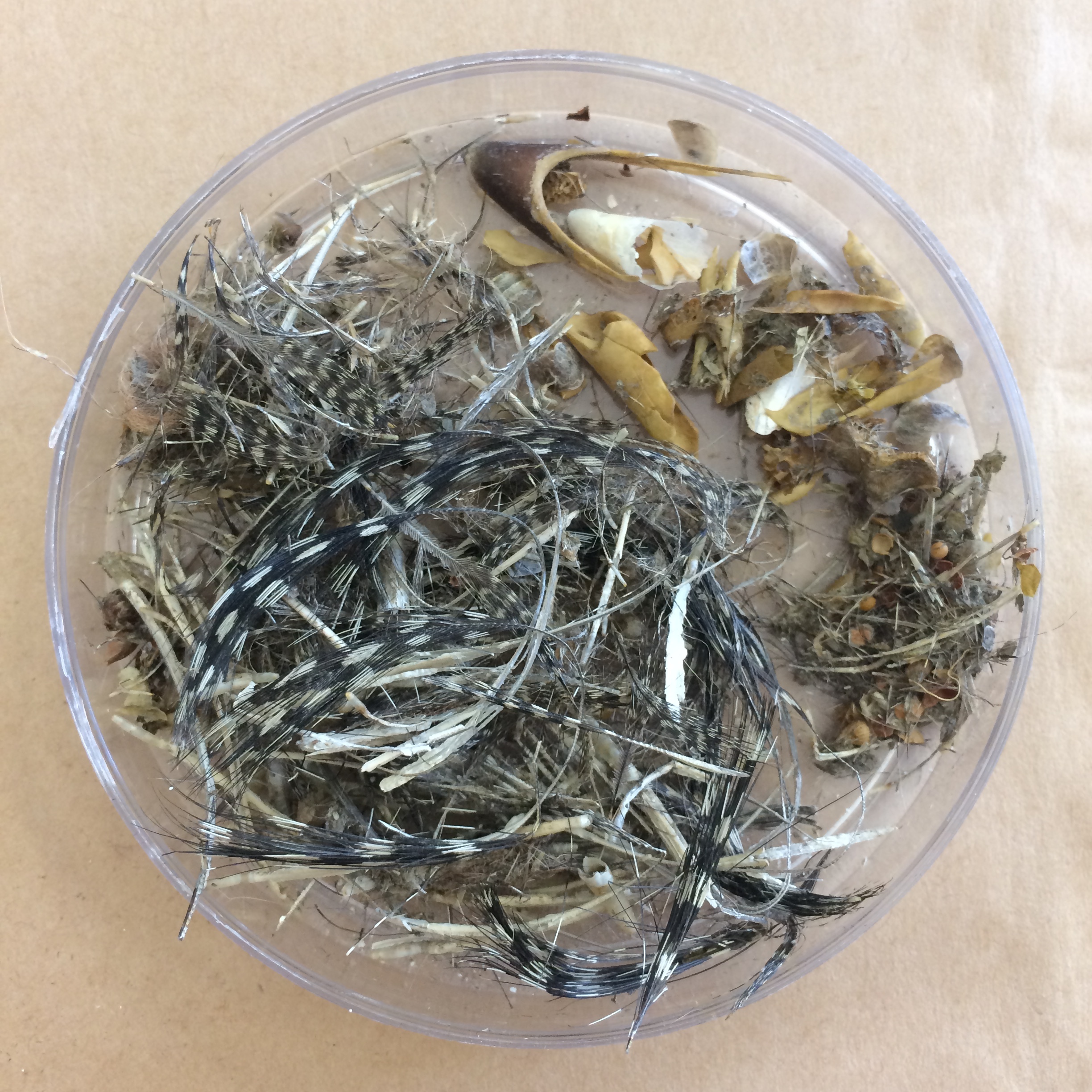

- May 29, 2017 When predator becomes urban caracal prey May 29, 2017

-

March 2017

- Mar 15, 2017 “Oh look, another cape cormorant”: some trips to the museum Mar 15, 2017

-

January 2017

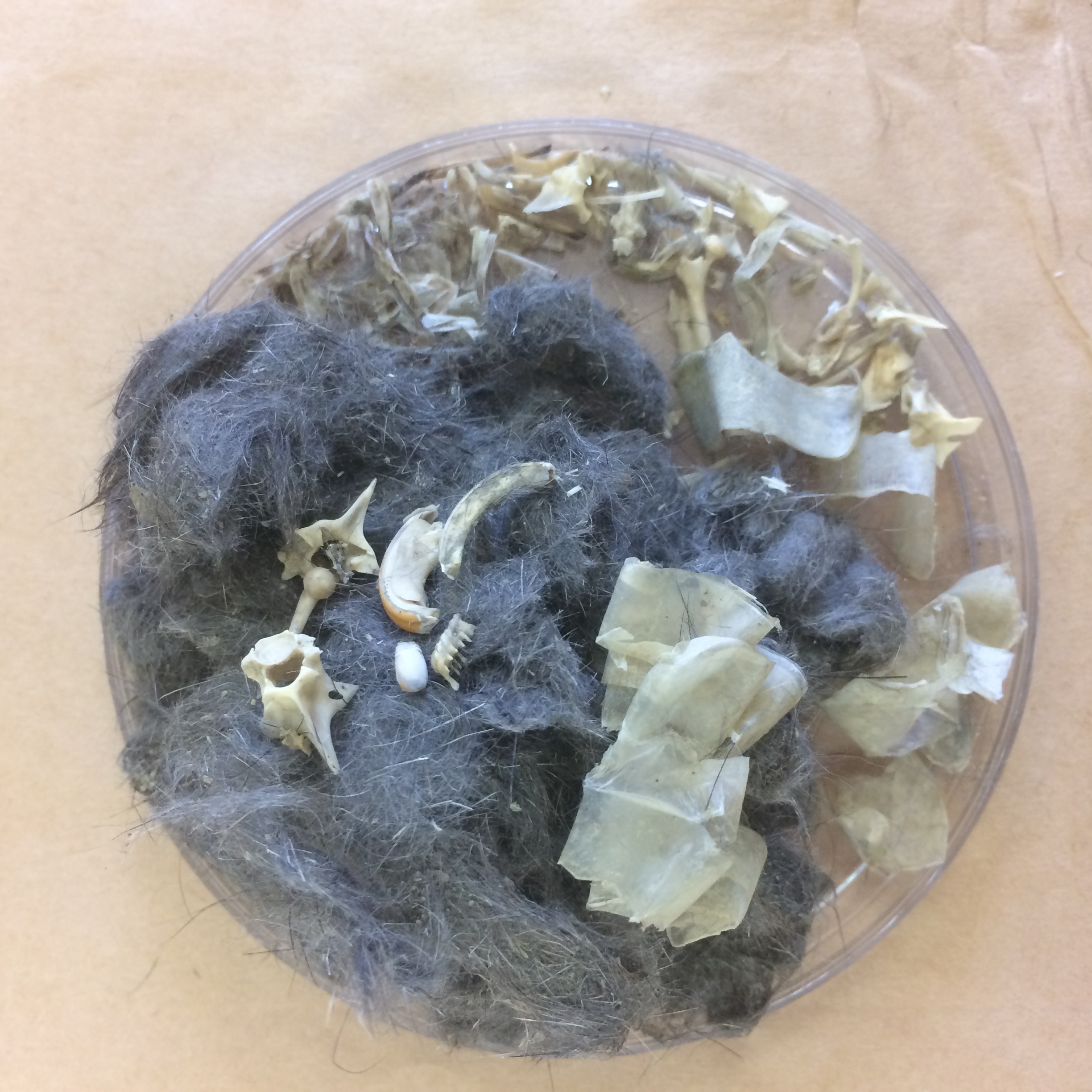

- Jan 31, 2017 Two charismatic caracals' favourite snacks Jan 31, 2017

-

November 2016

- Nov 3, 2016 A few more caracal lunches, and some mystery claws! Nov 3, 2016

-

October 2016

- Oct 3, 2016 Appreciation post Oct 3, 2016

-

September 2016

- Sep 26, 2016 SAWMA symposium 2016 Sep 26, 2016

-

August 2016

- Aug 31, 2016 Some (very) preliminary diet findings Aug 31, 2016

-

June 2016

- Jun 1, 2016 Caracal diet field trips Jun 1, 2016

-

May 2016

- May 31, 2016 No such thing as a free caracal lunch May 31, 2016